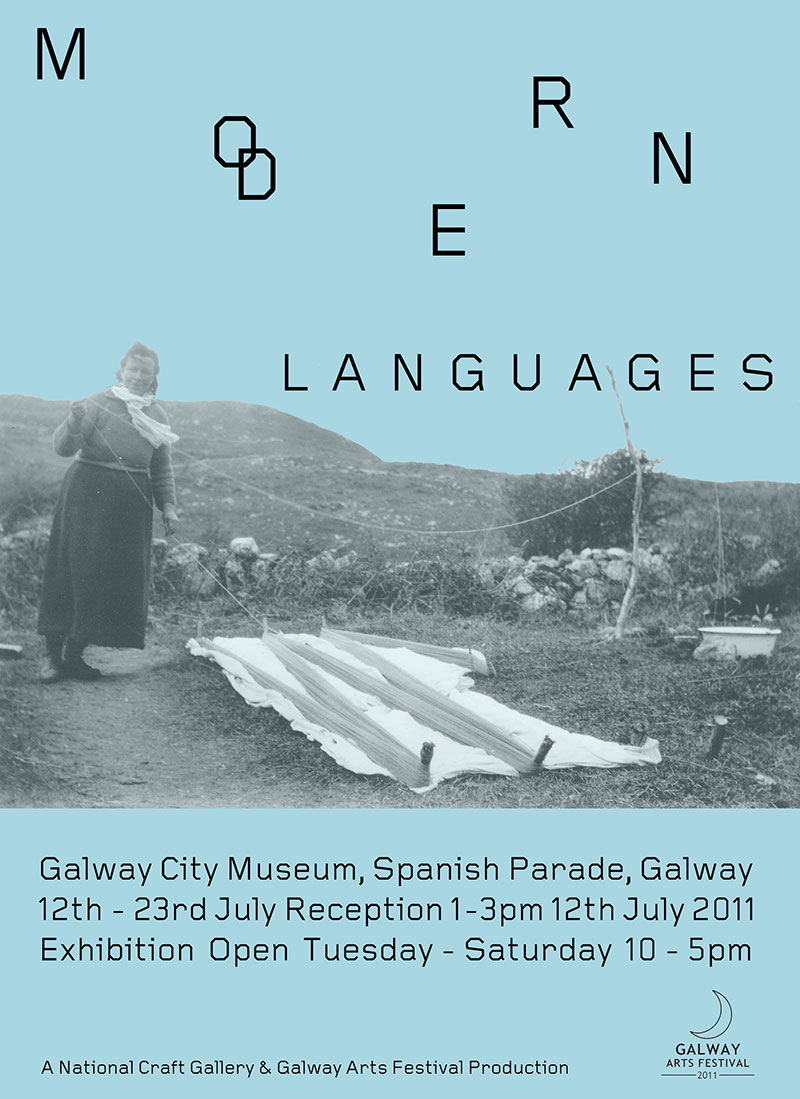

Modern Languages

Modern Languages

[threecol_two]

Reinterpreting the Irish Vernacular

Modern Languages presents the work of five artists and designers with varying relationships to Ireland. Coming from Ireland, Scotland, Canada and Japan, these artists offer new interpretations of traditional Irish craft.

The exhibition explores the relationship between indigenous Irish craft and contemporary international creative practice. It focuses on the international adoption and corruption of craft practices within the artist’s work; each adapts elements of the Irish vernacular to convey meanings that are no longer dictated by historic provenance but by their own personal interests and motives.

Ciara Phillips

Ciara Phillips studied Fine Art at Queen’s University, Kingston and at the Glasgow School of Art MFA programme. She is second-generation Irish, born in Ottawa, Canada, and currently based in Glasgow. The making skills she learnt from her mother and aunts as a child growing up are central to her work. She uses traditional textile techniques such as sewing, print and patchwork to explore language and communication, object and imagery as part of our wider cultural fabric.

For Modern Languages, she has spent time with weavers at Studio Donegal, on the production of designs for woven blankets. Her time there inspired her to look, not just at the fabric and weave, but to consider the nostalgia imbued in fabrics whose methods of production have changed little over time. The resulting work is a collection of unique blankets that are a reflection on the history and traditions of weaving in the area.

Deirdre Nelson

Deirdre Nelson graduated from Glasgow School of Art in 1992. Her practice has evolved through experimenting with materials and methods of making in which hand work and craftsmanship allow social commentary. Deirdre grew up in Northern Ireland with parents from the West and is now based in Scotland.

Taking inspiration from popular thatched-cottage souvenirs, Nelson’s moneybox depicts a modern new-build house, with an online knitting pattern available to help people save for more austere times.

For commercial reasons, pattern was incorporated into jumpers around 1900 by a group of women from the Aran Islands. Nelson has partly deconstructed an Aran jumper, re-knitting it in the more authentic, and historically accurate, plain stitch used up until that point. The edging of red wool references the vibrant skirts worn by the women of Aran.

Inspired by J.M. Synge’s play Riders to the Sea, where knitting flaws in a pair of socks helped the identification of a drowned fisherman, here detailing of dropped stitches has been incorporated into a pair of socks.

Barbara Ridland

Barbara Ridland has knitted since childhood, and graduated from Grays School of Art, Aberdeen in 1980, having specialised in drawing & painting. She has lived on Shetland for most of her life.

Ridland’s work has developed from basket-making traditions in Ireland and her native Shetland. These containers, made for carrying fuel, groceries and even small children, are important elements of the culture and history of both places. They began to fall out of use with the introduction of plastic and mechanised methods of transport, along with an entire vernacular language: such as Kishie (a basket for carrying crops) and related words Hjogs, Simmoins and Fletchie.

Ridland’s forms draw from notions of mythical creatures such as Pookas, Banshees and Leprechauns, or the Shetland equivalent, Finns, Nyuggles and Trows. They also reference the Irish Straw-boys or Shetland Skeklers – groups of revelers dressed in pointed straw hats and skirts, who arrived, uninvited, at Yule or Halloween, where they sang, danced and played the fool. The works, which incorporate openings and printed text, suggest mouths, words and vernacular languages, interweaving them through place and time like strands of DNA.

Laura Mays

Laura Mays has a MA in Industrial Design at the National College of Art and Design, Dublin, a degree in Architecture from University College Dublin and a Higher Certificate in Furniture Design and Manufacture from GMIT Letterfrack. She followed that with two years on the Fine Woodworking program in College of the Redwoods in California. During her masters she has worked to dissect and reinterpret Irish vernacular furniture, redesigning its structure and redefining its function. While staying true to the design, Mays has pushed the boundaries of the common chair’s form.

Mays has gone on to apply this way of working to understand a more contemporary and readily available chair – IKEA’s Stefan; the cheapest chair in IKEA, it retails at €16 and approximately 200,000 are sold per year worldwide. Stefan 1 becomes an object of high quality through the materials used and the skilled labour involved in its production. Smashed and meticulously put back together Stefan 2, acknowledges the increased value attributed to cherished objects. A rocking chair highlights the narratives that become part of an object’s history in Stefan 3 and, through splicing the chair’s profile with a human form, Stefan 4 highlights both the chair’s function and the complex relationship between the craftsman, object and technology.

Nao Matsunaga

Nao Matsunaga was born in Osaka, Japan and graduated from the University of Brighton in 2002 and from the Royal College of Art in 2007. His first visit to Ireland was a research trip for Modern Languages.

Nao works with clay, brick, wood and other materials. He creates raw organic forms in which surface texture is highly important. These sculptures are often juxtaposed by angular details inspired by architecture, and it is this combination of natural forms and man made structures that interests him.

The currach, indigenous to Ireland, is a wooden framed boat covered in a skin of animal hide or canvas and treated with tar and grease. Shelter with Multiple Legs (Beach Animal) incorporates the zoomorphic qualities of beached currachs, and also refers to the way in which they are carried to and from the shore. Forlorn Tree is a series of works using bitumen and pine, referencing the economical use of raw materials used in the boat’s construction.

Katy West

Curator

Modern Languages offers the perspective of five international artists and designers with an interest in craft, its history and meaning. These artists seek to re-interpret the sometimes familiar, sometimes forgotten skills of Ireland’s craft tradition. In doing so they uncover fresh significance and meaning, offering new insights into the Irish vernacular.

The premise for the exhibition came about through watching Michel Flaherty’s seminal 1932 film Man of Aran. It is a film steeped in the vernacular, from the fishermen’s sweaters to the dry-stone walling. But what enticed me most was Flaherty’s unapologetic use of the materials the Aran islanders had to hand. Although dubbed the first ‘Mocumentary’, Flaherty’s film is faultless in its poetic use of materials. It projects the universal idea of man’s struggle against the sea through a carefully constructed fictional reality.

These careful re-enactments of tradition against the backdrop of a harsh natural landscape made me consider the contemporary artist, designer or craft person’s use of traditions and known signifiers. Like Flaherty the artists in Modern Languages appropriate and re-contextualise known elements from within the vernacular tradition to better communicate their own concerns and interests.

Ciara Phillips’ work with Studio Donegal uses their traditional hand-weaving techniques and employs the Studio’s range of existing yarns. Phillips enlisted the support of master weaver John, to carry out work from designs developed by Phillips in consultation with Studio Donegal. During the collaboration a respect and understanding of each other’s ideas and techniques was forged. In Phillips work with Studio Donegal the concerns of the vernacular tradition and contemporary artistic practice are shown as mutually supporting.

The contributors to the exhibition hold varying ties and relationships to Ireland. Whilst Nao Matsunaga’s initial unfamiliarity with both the Aran Islands and Irish traditions in general has resulted in a formalist interpretation of the canvas-on-frame Irish currachs, Deidre Nelson’s textile works draw on an array of cultural traditions, myths and clichés to make sense of her contemporary surroundings.

Matsunaga is a sculptor who works predominantly with clay. His hollow clay forms with apertures, combined with wooden stick legs share a common vocabulary with the slick beetle-like currach as it is carried down to the strand on the backs of men. For Modern Languages Matsunaga’s response to the west coast tradition of currach making plays fast and loose with vernacular tradition, intuitively responding to formal similarities or material juxtapositions to create idiosyncratic assemblages.

By way of contrast Nelson’s focus is on the myths and cliches of her home country Ireland, reinterpreting its culture with a close eye on the malleability of its traditions. Nelson’s realisation that the Aran knit was developed more as a profitable souvenir than out of practicality (the plain grey ganseys had served perfectly well for years) has led to a set of products that negotiate ideas of both ‘authentic’ Irish heritage, and the Irish heritage industry, to produce a collection of ‘souvenirs’ that link directly to the economics of both traditional cottage industry and the more recent turmoil of contemporary Ireland.

Viewed comparatively the challenges facing Irish craft traditions are in no way unique. Shetland based Barbara Ridland takes pleasure in the endless beauty within the ordinary artifacts from her textile, crofting and maritime heritage. She acknowledges that many such artifacts remain for the sake of tourism or as collectables, their function having been replaced by more efficient and affordable objects in plastic. With the demise of the practical use of traditional artifacts a whole vernacular language has almost fallen out of use at the same time:

”Kishie, Gloy, Hjogs, Simmoins, Buddie, Meshie, Fletchie, Cuddie, and Fettel”

In Ireland too machines and mass-produced imports have replaced the work of the local craftsmen, and synthetic materials replace natural locally sourced products. Using computer controlled cutting to create a series of profiles which are then built up into a version of the IKEA Stefan chair Connemara based Laura May’s Stefan 4 explores both the relationship between new technology and craft, and also the relationship between the chair and the body of its user.

By re-inserting an image of the user’s body into a mass produced artefact Mays re-inscribes into mass production the image of a unique, personal relationship. Similarly Ridland takes a dying and practically obsolete artefact, the Shetland basket-form kishie, and re-animates it using the discarded scraps of cardboard packaging made ubiquitous by contemporary consumer culture. In this way one form of obsolete container (discarded packaging) is transfigured into the image of another (the now almost abandoned craft of Kishie). Such transfigurations from past to present, from commonplace to unique, from material to idea and back again provide a testimony to the valuable ongoing role that traditional craft skills play in providing contemporary artists and designers space to reflect upon their role in relation to contemporary society. Modern Languages seeks to demonstrate the modern language of craft, transcending place, and employing a wide variety of materials and methods to explore ideas and concepts through making.

The Complexity of Time

Eleanor Flegg

2011

Not all people exist in the same Now. They do so externally, through the fact that they can be seen today.

Within the last fifty years, craft in Ireland has become professional. Activities once undertaken within a simple rural lifestyle have become part of a contemporary practice, adopting the language and the intentions of art. Some crafts have fared better than others. Basketry, for example has been transformed almost effortlessly and without losing its traditional forms. A few have held their functional value. The work of the saddler and the musical instrument maker has no need to reincarnate as expressive art; it is still in demand for its original use. Other crafts have struggled. Where is the twenty-first century incarnation of the cast iron pot or the cooper’s barrel?

Those crafts that have not found a place in contemporary practice remain in the vernacular which is, in sense, the reject pile. Vernacular objects are those that have not made it into the cannon of contemporary craft. But yet they belong to the vocabulary that helped to form it. Once craft is made in the twenty-first century, by a maker trained at third-level to articulate the ideas behind the piece, it is no longer purely vernacular, no matter how traditional the skill of making. But the vernacular does not remain in the past; it is more fluid and slippery than that. There is a new vernacular in hobby craft and in populist forms of making that do not privilege aesthetic hierarchies. The work in Modern Languages does not belong to either the old or the new vernacular, both of which are characterised by a lack of irony. The exhibition shows self-conscious sophisticated objects that honour their ancestors. Although much of contemporary making stems from the love of everyday objects and the ways that they were made, it is rare to see this openly acknowledged. Craft, in its current manifestation as art, has often remained a little aloof from its vernacular roots. The contemporary craft world privileges the innovative, and the vernacular is tainted with the stigma of the old and unwanted. Part of the value of Modern Languages is that it is an overt expression of the deep and abiding love for the common tongue.

There is no single language of vernacular craft: it is a tarpaulin term stretched over an array of objects which had little relation to each other at the time that they were made. Many practices are nostalgically imbued with non-specific ideas of rural tradition, which masks their fascinating diversity. Basketry is often considered a ‘country craft’ practised as part of a rural way of life, but it also belonged to an urban vernacular. Ioldanas (1970) an exhibition that marked the first World Crafts Council congress in Dublin, included a log basket and a herring cran basket by Joseph Shanahan. These were not country crafts: the Shanahan family had owned a basketmaking business in Carrick-on-Suir since the late nineteenth century and had, at one time, been a sizeable local employer. Their baskets were functional items, made for their original purpose. It was, however, a craft practice coming to the end of its cultural lifespan: the cran, which was the standard weights and measures basket for the sale of herring, was due to become obsolete when Ireland joined the EEC in 1973. Joseph Shanahan’s baskets at Ioldanas were transitional pieces in that they were made as utensils but displayed as art. This pointed towards a possible future direction for the discipline.

It is essential that baskets continue to be made: unlike ceramics, they don’t last forever and the most secure way of preserving them is to perpetuate the skill of making. But the reasons for baskets have changed: a contemporary herring cran is likely to be sold as a souvenir or an expensive collectors’ item. This has changed the demographic of basketmaking. Baskets were once highly specific to local requirements which dictated their forms, and the skills were passed down locally. The different forms of making are now more likely to be handed down within an international community of artists, who have become, almost by default, the custodians of the discipline. Among them, Barbara Ridland’s work draws upon the woven straw work of Ireland and Shetland, and its use in ritual costume. Her containers, some of which have mouths, reflect the connectivity of objects and language and the way in which, the patterns and techniques of making run like strands of DNA: inherited, traceable, and gradually transforming.

The concept of authenticity, given a good hard shake and held up to the light, is utterly inappropriate to the vernacular tradition. Authenticity implies something that is fixed. A cabinet is either made by a certain cabinet-maker or it is not. But vernacular forms are not fixed; they are like a piece of traditional music and different in every rendition. A recent series of chairs by Laura Mays explores the recurrent patterns within chairmaking within the vernacular, and how this differs from the reproduction of specific designs. A Sligo chair, which already has many variations, is not a fixed form: just as a performer interprets a tune, neither following to a strict score nor playing something entirely new, each new chair has both similarities and differences to its predecessors. The use of the pattern enlarges the category of Sligo chair, just as each time a traditional tune is interpreted its meaning is expanded. In this way, Mays’ rendition of the pattern is part of a wider evolution of the pattern over time.

But the visual similarities between a contemporary chair, made with expressive or philosophical intent, and its vernacular antecedent can also be misleading. Some vernacular objects have an aesthetic integrity that allows them to be lifted unaltered from the workshop to the gallery plinth, although they were not intended as art objects and were made with a different set of priorities. In 1974 a pair of Leitrim chairs made by John Surlis travelled to Canada, to feature in the World Crafts Council exhibition In Praise of Hands, where he was awarded one of the major prizes. The catalogue for that exhibition states that: ‘The chairmaking tradition of the Surlis family, handed down from father to son, goes back six generations.’ But, while this seems to establish a professional identity for the Surlis family as makers of furniture, David Shaw-Smith’s film, The Leitrim Chair (1980), records that the Surlis family were coopers and that the chairs were a relatively recent side-line. Surlis described chair making as ‘more of a hobby than anything else’. He also made miniature versions of the Leitrim chair for sale in the family shop, as well as toy-sized donkey straddles and sugán chairs. These pieces, although skilfully made and appealing, fall into a category of souvenir that would be considered kitsch.

Surlis’ chairs are an example of one of the many instances – and this is explored in the work of Nao Matsunaga – in which vernacular forms show an unselfconscious Modernism. Their form and their function have never been disentangled. Surlis entered his work for the Toronto exhibition because he was encouraged to do so by Muriel Gahan, the founder of the Country Shop. Gahan, a shrewd judge of craft aesthetics and workmanship, had an ability to see the ‘possible modernity within craft’. ‘She sent an organiser,’ Surlis wrote, ‘by bye-ways and highways looking for craftworkers and she came to Monasteraden. Some years later through Miss Gahan I gave a demonstration at the Dublin Horse Show. I was treated so well before leaving Dublin that I promised her that anything that I made in the future would be better the next time.’

Gahan also played a part in the development of the Aran sweater, which is a more recent element of vernacular heritage than often supposed. The intricately patterned báinín sweater was developed in the 1930s as a cottage industry, supported by the Country Shop; prior to this, the men of the Aran Islands wore dyed wool sweaters with a patterned section. The white sweater, probably inspired by those worn by boys at their confirmations, became fashionable among the young men of the islands. Tradition is a moveable feast and what is understood as authentically Irish is often of mongrel extraction: invented, manipulated, or imposed. There are few pure lines of lineage. But the objects remain, often more interesting when not understood through a system of cultural eugenics.

The work of Deirdre Nelson unravels some of the mythology behind the construction of knitting and lace, the Irishness of which is both more complex and more interesting than it might be supposed. Kenmare lace, for example, originates in an industrial school, opened by the Poor Clare nuns to relieve destitution in the 1860s. As the nuns began to develop their own designs, the school became known for needlepoint technique and original design. The lace, which was highly regarded in the nineteenth century, was mainly sold abroad. Alan S. Cole, author of A Renascence of the Irish Art of Lace-Making (1888) wrote that: ‘the Emerald Isle of the United Kingdom can revive, in modern expressions, glories of historic Venetian Points, Italian Cut Works, and Points of Alençon and Argentan.’ Cole observes that a needlepoint collar, designed by one of the nuns at Kenmare, was suggestive of a variation in needlepoint lace-making developed in France in the reign of Louis XIV. Lace continued to play fast and loose with tradition. Another Irish piece shown in In Praise of Hands, a needlepoint lace collar in gold Lurex yarn, was worked in Kenmare buttonhole stitch by Sister Rosaleen McCabe of Dublin. The collar is an adventurous synthesis of traditions. It draws on the nineteenth-century conventual tradition in terms of technique, but the outline of the piece is that of a pre-Christian Bronze Age lunula, while its patterning is based on the head of the twelfth century Lismore Crozier. McCabe’s innovative use of gold Lurex yarn provides a visual link between the medium of lace and its references to historic metal. The exhibition catalogue juxtaposes the lace collar with pieces of modernist jewellery, but it is not clear to what extent the pieces shared a conceptual framework, and to what extent they merely looked as though they did.

The cultural lineage of tweed is also more complex than it appears. Handwoven tweed is often accompanied by romantic images of Irishness: sheep on an open mountain, or weavers at their loom, and Judith Hoad (1987) wrote that it had a quality that set it apart from the machine made: ‘It is an intangible quality for which there is no word in English. Few people have the awareness to recognise it, but many are deluded by the illusion of it.’ In the mid twentieth century Irish handweaving, traditionally a male-dominated craft business was gradually replaced by mechanical weaving, while handweaving as a female-dominated studio craft gained in popularity. In the 1970s a generation of studio makers transformed Irish weaving from a business, using outworkers to produce miles and miles of tweed, to an expressive art practice. These makers were mostly women, and nearly all of them worked on Swedish looms. There were several reasons for this. The fly-shuttle loom, traditionally used in Ireland, was heavy to use and generally required male strength. The Swedish looms were domestic in scale and were typically used by women to make cloth for the household. They were better suited to one-off pieces than the fly-shuttle loom, which was designed to produce cloth by the metre. By going back to Donegal Weavers, one of the few places in Ireland where the fly shuttle loom is still operated commercially, Ciara Phillips is reversing the trend. Her work, which disrupts the symmetry of the weave, takes a step back from the trope of the solitary studio worker, and re-enters an older layer of tradition where cloth was the work of many people.

Henry Glassie (2000) writes that: ‘Examined closely, analysed formally on the grounds of compassion, then manipulated into cultural arrangements, material culture breaks open to reveal the complexity of time, its simultaneous urges to progress, revitalisation and stability.’ All objects, vernacular and sophisticated, are expressions of culture. They carry their ancestors within them.

[/threecol_two] [threecol_one_last]

Galway Museum

Galway Arts Festival

July 2011

National Craft Gallery of Ireland

Kilkenny

October 2011

Linlithgow Palace

Linlithgow

October 2012

Timespan

Helmsdale

December 2012

The Lighthouse

Glasgow

January 2013

An Tobar

Isle of Mull

August 2013

Archival film footage

with exhibitor’s interviews (18 min)

Images:

Ciara Phillips

John

Screenprint on paper

(2011)

Deirdre Nelson

Aran 0.5

Re-purposed eBay Aran Jumper

(2011)

Deirdre Nelson

Surplus

Wool

(2011)

Deirdre Nelson

Identity

Aran wool, from Kerry Woolen Mills

(2011)

Nao Matsunaga

Shelter with Multiple Legs

(Beach Animal)

Wood, ceramic, ink

(2011)

Nao Matsunaga

Forlorn Tree 1,2,3

Wood, canvas, bitumen paint

(2011)

[/threecol_one_last]